Hari Sabtu lalu, 16 Desember 2017, 5th Urban Social Forum (USF) terselenggara di Bandung. Dalam satu hari duapuluhdua panel diskusi dan tiga lokakarya berlangsung, meminjam ruang-ruang kelas pada sebuah sekolah menengah atas negeri. USF adalah acara tahunan yang diselenggarakan oleh Kota Kita, sebuah yayasan beralamat di Solo (Surakarta). Salah satu tujuan Forum adalah untuk mempopulerkan isu-isu perkotaan dan untuk itu Siska dan Kristo hadir dalam panel yang mengupas isu seputar hak atas kota dan panel tentang kepemilikan tanah di kota mewakili Architecture Sans Frontières Indonesia (ASF-ID).

Forum dibuka oleh sesi pleno yang menampilkan Gugun Muhammad dari Jaringan Rakyat Miskin Kota, Hera Diani dari media Magdalene, Savic Ali dari komunitas Gusdurian, dan Somsook Boonyabancha dari Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR). Pleno pembuka berjudul sebuah pertanyaan; Kota ini milik siapa?

Gugun menyoroti ketimpangan penguasaan lahan, seperti halnya terjadi di Jabodetabek. Juga ada ketimpangan narasi tentang warga miskin kota sehingga opini publik jauh dari kenyataan. Misalnya yang terkait ukuran rumah, pola pemakaian ruang, dan budaya bermukim, “ada cara hidup yang dipaksakan, lalu (mereka) bilang bahwa rumah-rumah, kampung miskin itu tidak standar.” Para pejabat publik dan pakar yang notabene merupakan anggota warga kelas tengah turut memberi andil terhadap latennya persepsi yang bias tentang kampung kota dan warganya.

Dua pembicara berikutnya juga risau oleh berbagai bentuk ketimpangan yang masih berlangsung dan kentara di kota-kota; Hera bersaksi tentang prevalensi pelecehan seksual, misalnya saat kaum perempuan menggunakan sarana transportasi publik; Savic melihat bahwa seiring meningkatnya tren politik identitas primordial SARA terjadi penurunan sikap toleransi yang muncul dalam bentuk ancaman, gangguan, hingga kekerasan oleh gerombolan dengan atribut agama terhadap sekian kali penyelenggaran kegiatan oleh kelompok masyarakat sipil di ruang-ruang publik ibukota.

Sesi pleno ditutup dengan sebuah resep dari ACHR untuk suatu perubahan yang mendasar bagi kota-kota; ruang-ruang partisipasi bagi warga harus diperluas, termasuk lewat inovasi model pendanaan perbaikan slum, kampung miskin kota. Demikian, tanah dan hunian diyakini sebagai unsur utama yang akan membuka akses terhadap beragam hak lain dalam rumpun hak atas kota.

Hak (Kolektif) atas Kota

Membicarakan hak kolektif atas kota, Panel-3 dipandu oleh Ahmad Rifai dari Kota Kita. Panel menghadirkan Hirson Kharisma dari Lembaga Bantuan Hukum (LBH) Bandung. Gatot Subroto dari Paguyuban Warga Strenkali Surabaya (PWSS) dan Fransiska Damarratri dari ASF-ID.

Hirson memberi gambaran model advokasi yang belakangan ini berlangsung di Bandung; di samping keberadaan LSM yang mapan juga ada beberapa kolektif di Bandung yang bergerak secara otonom. Dipersatukan oleh isu, kelompok-kelompok tersebut beraliansi untuk kepentingan publik dan warga pada beberapa kasus a.l. terkait kontroversi lahan eks-Palaguna, serta pada penggusuran Tamansari, Kebon Jeruk, dan Dago Elos. Menurut Hirson, hak atas kota harus direbut lewat partisipasi warga dalam rangka melawan praktek pembangunan yang neoliberalistik.

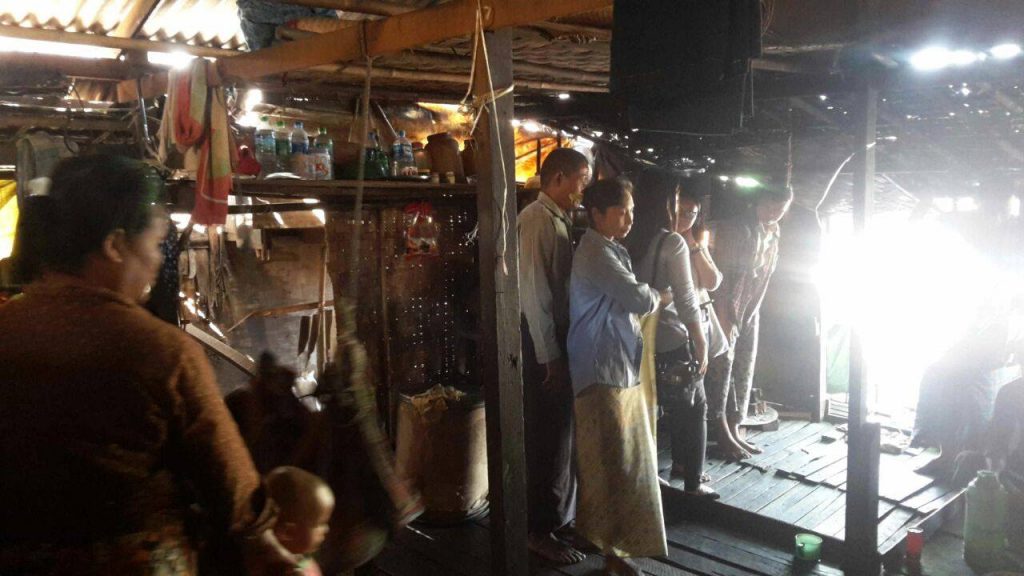

Di Surabaya, PWSS menghimpun sejumlah kampung sepanjang bantaran di Kali Mas dan Kali Surabaya yang sudah berumur lebih dari 30 tahun. Pada tahun 2005, PWSS mengajukan konsep kerja partisipatoris jogo kali dan kemudian berhasil mendapat pengesahan perda. Implementasi jogo kali diwarnai dengan kegiatan pengolahan sampah, kerja bakti, hingga ritual larung sungai sebagai simbol kedekatan dengan alam. Anggota PWSS telah membongkar rumah mereka sehingga menghadap sungai sekaligus menyediakan jalur untuk keperluan inspeksi sungai.

Dua tahun lalu ASF-ID mengadakan kampanye putar film dan diskusi sebagai respon kritis terhadap fenomena rusunisasi. Kini ASF-ID tumbuh sebagai jaringan kerja meliputi kota Bandung, Jakarta, Malang, dan Semarang. Perkumpulan terus memperluas wawasan yang utamanya dibutuhkan oleh para arsitek untuk melampaui perkara estetika. Mengingat arsitektur pun hidup di ruang sosialnya yang diskursif, di kota maupun di desa.

Lewat kerja ASF-Jakarta, Rumah Contoh di Kampung Tongkol menjadi sebentuk upaya politik yang melampaui upaya estetik. Capaian di Jakarta menjadi pintu bagi grup lokal untuk bersinergi dengan berbagai komunitas dan kelompok warga hingga inisiatif tersebut bergulir menjadi upaya contoh perbaikan pada 16 kampung serta mendapat dukungan anggaran daerah. Pada tataran lain ASF-ID mengembangkan metode pemetaan partisipatoris bersama warga. Lewat kegiatan tersebut relawan arsitek maupun mahasiswa memperoleh kesempatan untuk mengupas aspek-aspek lain dari lingkungan binaan, misalnya aspek sejarah perubahan dan kontestasi lahan yang terjadi di kota seiring waktu berjalan.

Dalam berinteraksi dengan warga, aktivis acap kali berurusan dengan upaya menggeser paradigma. Bagi Hirson, sebelum warga memperoleh pemahaman terhadap hak, bersama-sama perlu membiasakan sikap demokratis. Terkait paradigma relasi sosial yang egaliter dan untuk kelestarian alam, menurut Siska, kelompok aktivis dapat saling belajar dan menempatkan kampung sebagai sumber inspirasi. Alasannya, pengetahuan dan keahlian lokal sudah ada dan dijalankan di kampung sebelum ada dominasi ilmu pengetahuan formal, sebelum kehadiran kaum profesional.

Tanah di Kota Untuk Siapa ?

Saat ini ketimpangan akses terhadap lahan menjadi fenomena yang melazim di berbagai tempat terutama di kota-kota. Demikian yang disampaikan Achmad Uzair dari Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga saat membuka panel Untuk Siapa Tanah di Kota? Panel menghadirkan perwakilan warga, peneliti desain ekonomi Bintang Putra, peneliti agraria Handika Febrian, dan Kristoporus Primeloka dari ASF-ID. Uzair mengajak hadirin untuk melihat keragaman akses terhadap tanah yang kini terancam oleh kecenderungan sistem hukum yang semakin formal dan legalistik.

Perwakilan warga dari Paguyuban Pringgomukti dan Kalijawi menyampaikan sebentuk gugatan mewakili kaum penghuni penggarap turun temurun dalam status lahan ngindung dan sultan grond, kemudian pendirian hotel menyebabkan penggusuran. Kepala desa kerap terlibat dalam penjualan tanah kas desa. Sementara itu partai politik abai terhadap permasalahan agraria yang dialami oleh warga Yogyakarta.

Menurut Handika, sebagian dari akar permasalahan agraria adalah adanya dualisme hukum. Di Yogyakarta hukum agraria yang feodalistik terkait status keistimewaan saling bersaing dengan hukum nasional yang berlandaskan UUPA 1960. Dengan demikian ada hambatan politik dalam pelaksanaan hukum agraria, padahal UUPA’60 menganggap penting mereka yang menempati lahan serta beritikad baik dalam mengelolanya.

Di Jakarta, sekitar 50% tanah tidak bersertifikat dan dengan kata lain dapat disebut ilegal. Yang mengherankan, demikian mudahnya pengadaan tanah untuk pembangunan mall atau apartemen. Kemudian ada sejumlah lahan milik pemerintah yang berdasar kesepakatan di masa lalu dikelola oleh pengembang, namun setelah berakhir masa perjanjian tanah tidak dikembalikan, juga tidak dibayarkan retribusinya. Di tengah surutnya pengusasaan lahan oleh pemerintah kota, di saat memerlukan, pemerintah kota merebut kembali lewat penggusuran paksa. Sehingga pada tahun 2015, merujuk data yang dikumpul oleh LBH Jakarta, terjadi angka pengusuran paksa terbanyak di seluruh wilayah DKI Jakarta. Angka penggusuran paksa tertinggi datang dari Jakarta Utara.

Kode warna yang mewakili zonasi peruntukan pada peta rencana detil tata ruang seringkali diubah dan ditentukan oleh pemerintah secara sepihak lewat proses yang tidak transparan dan tidak akuntabel. Misalnya seperti yang terjadi pada peta Kampung Kerang Ijo di Muara Angke, Jakarta Utara. Di dalam rencana tata ruang kampung tersebut ditetapkan menjadi zona biru, dianggap menjadi bagian dari laut, padahal ada ratusan keluarga hidup disana. Pada banyak kasus disinyalir oknum kelurahan dan kecamatan bersekongkol dengan oknum Badan Pertanahan Nasional (BPN) untuk menyediakan tanah yang telah “dipesan” oleh sebuah pengembang. Lewat kolusi tata ruang seperti ini, diprediksi penggusuran akan terus terjadi di kemudian hari.

Kristo menekankan pentingnya usaha meluaskan perspektif di kalangan arsitek dan desainer karena meskipun jarang terlibat dalam proses pengambilan keputusan, namun arsitek dan desainer tetap terlibat dalam perubahan dan penguasaan ruang yang terjadi di kota. Sebagai aktor dari gubahan dan pengelolaan ruang kota, seorang arsitek atau perencana memiliki potensi dalam memaksimalkan penggunaan dan pemaknaan ruang. Arsitek berpeluang untuk menjadi pembuka ruang partisipasi lewat pemilihan bahan dan teknologi membangun dalam rangka menjaga aksesibilitas terhadap ruang kota. Pada titik ini keberpihakan kaum profesional menjadi penting dalam gerakan advokasi untuk kepentingan warga kota. /////